Play & Energy of the Unknown

Text and visuals by Zack Wood

March 31, 2016

Though its outward form varies, the structures that give rise to itーthe settings, attitudes and expectations best suited for playーare similar to each other while at the same time dramatically different from those suited for manipulating physical energy through machines and labor.

Dancing into play

First, imagine you are on a small street filled with people in celebration, eating, laughing, and talking. Suddenly, in the distance you hear the distinct clang of a metal bell, and then the echo of drumming. A simple rhythm and faint melody grow louder as they come closer, up the hill, around the bend into your view. And then there it is, lumbering slowly through the streets, a beast that ignites all who encounter it with a surge of joy that impels them to dance.

The dance itself is familiar to most people in Japan thanks to being performed at festivals (typically the Obon Festival, a major festival in summer). This means a parading train of Awa Odori performers instantly creates a space that is both familiar and marked for celebration outside the realm of everyday life (what’s called the “magic circle” in game theory).

The dance is essentially a series of steps forward with accompanying hand gestures that are repeated over and over, allowing the group to parade down streets. Performing the dance for long periods is of course physically taxing, and mastering it takes a lot of practice; we spent many afternoons and nights practicing together to get these basic steps right. However, the undeniably straightforward and repetitive nature makes for a low barrier to entry for those who want to dance along.

The other core element of the dance is the call and response, a few sets of phrases shouted back and forth between one performer and the rest of the group (and members of the crowd), which happens on and off whenever people feel moved to initiate it by shouting the first line.

The repetitive nature of the danceーand the amount of practice that goes into these simple stepsーfrees you as the performer from having to think about what to do next, allowing you to focus more on each action you take. This in turn enables you to invest more expressive energy into each action, achieving a level of intensity not possible in normal situations, and the feeling of vulnerability that accompanies this push into the unknown makes the rush of support from others during the call and response all the more powerful.

Playing to make a game

In other words, our team’s approach relied on internal motivation and a clear shared vision to fuel creative development in a way that was sustainably energizing. For me, the week was characterized by a state positive tension, both during productive periods and when relaxing; it was like children going down a slide, where climbing back to the top to go down again can be just as thrilling as going down the slide in the first place.

Another way of looking at the process is that we located an area of overlap between our perspectives and built upon it, creating something new in this shared space and thus expanding each of our perspectives as a result. Just as with Awa Odori, a sense of calm and joy persisted for some time even after leaving the venue.

Play and the joy of confusion

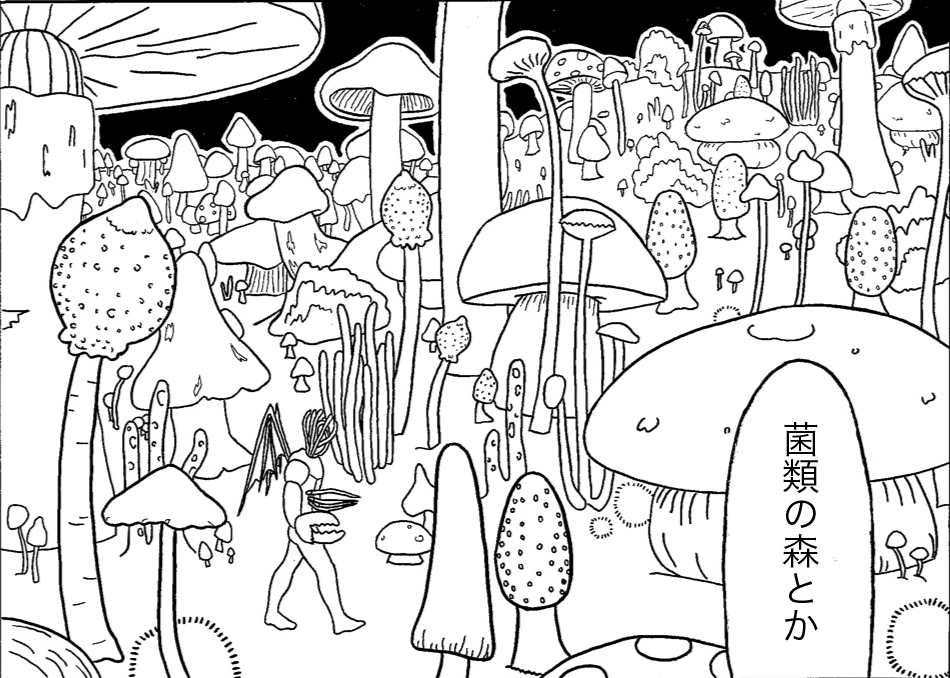

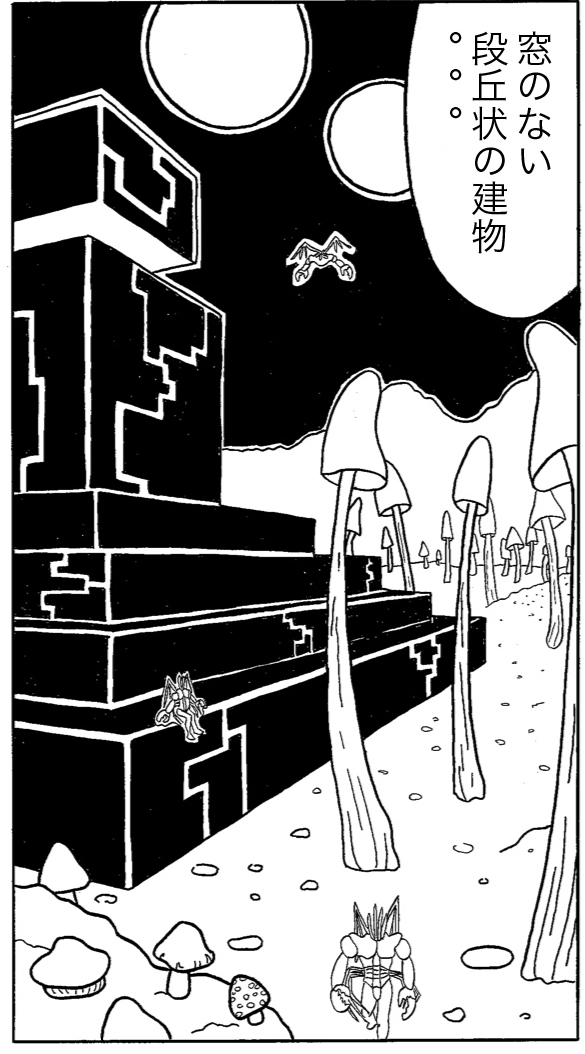

Finally, imagine that an entity from another dimension has appeared on the street where you live. Though you can’t see it, you can always sense its presenceーeveryone passing by can, as if a border has been crossed or a switch flipped.

Sometimes the entity appears to you in physical form as a young man who gives you a strangely personal but playful message, or a child who breaks out suddenly in a delightful song, and at other times everything goes dark as a loud rhythm fills the air and you can’t help but dance. Eventually you realize that the entity can move, and when it goes far enough away you find everything back to normalーpedestrians are just pedestrians, there are no sudden changes to the light, and no strangers stopping to share a story with you… But is that a faint hum of singing in the air? And did that person just give you a knowing smile? You try to follow but can never quite tell on which side of the boundary you stand.

Unsure who the performers were, I ventured onto the courtyard myself as the singing slowly coalesced into a more intense rhythm, seemingly improvised but performed in calculated unison by the hidden interpreters lounging amongst us. Suddenly it became clear who was who as the interpreters began to stand together in song and dance.

They then began to gather at a staircase at one side of the courtyard and one by one disappeared into a darkened doorway there. The setting became more intimate and quiet as the numbers of both performers and spectators dwindled until only one young woman remained singing at the foot of the stairs with a few people gathered around her. Eventually she too went through the black doors, and I followed.

Finally the interpreters left the dark room and made their way to the large stairs at the entrance of the museum, where they performed one last act, a song and dance off. Here for the first time I could see them clearly and up close before the performance came to a close.

I left the museum in a daze, confused by the performance’s blurred divisions between audience and performer, and questioning what it means for something to be “part of the show” as opposed to “real.” I was also struck by the vision of how strangers can engage in public space through the power of song and dance. The point is that the performance created playful structures that enabled and encouraged this kind of reconsideration and re-envisioning, making shifts in perspective and expectations feel like the most natural and joyful thing in the world. It also left me, once again, and more intensely than either of the previous experiences, overwhelmed with a sense of calm and warmth.

Structures for play

As different as these experiences may seemーalternately active and passive, materially productive and completely intangible, with friends and among strangersーthe structures that gave rise to each are surprisingly similar.

Many play theorists have also noted the voluntary nature of play, emphasizing that it can’t be forced. In a similar vein, all of the situations above offered an invitation to participate within a safe space where people could determine their level of involvement. Support from other dancers, the familiar nature of the dance and its role in festivals created a space where we as Awa Odori performers could feel safe going “out of control.” Establishing a shared group vision that was both clear and flexible while also being strict in giving ourselves down time to recharge allowed us as game developers to explore the unknown and discover something new in Sweden. And finally, Seghal’s interpreters’ open invitation to follow them through the museum and the blurred boundaries of their performance let us as audience members safely and comfortably engage with the joyful push and pull on our expectations.

The invitation to step into the unknown without knowing where it will be lead is, I think, at the core of play. Though often characterized as an act of agency upon an object or towards other players, play is in a sense an act of submission as the body and mind are allowed to go fall into the unknown without predictable results. Another way of understanding this unknown is as the realm of the potential, the universe of things that could be and creative connections that have yet to be made. To play is to access this world, catch a glimpse of what is possible, and physically embody the transfer of energy from potential to real, creating in the process a performance, a video game, or simply a shared experience of joy.

Going outside the limitations of one’s known world in this way can of course be frightening and stressful, which is precisely why structures of safety and trust are so important. This is why the focus provided by limitations helps us to process the unknown without being overwhelmed by it, and why a clear separation from everyday life helps us to mentally prepare for play.

As Rachel Shields suggested in her essay in the American Journal of Play, the human body is the interface between the physical world and the infinite world of the potential, and play is the realization of this potential. Safe spaces for play are where the unknown becomes knowable, the frightening becomes familiar, and personal and social transformation becomes an act of joy. When it happens, accessing the energy of the unknown through play feels like the most natural thing in the world; it almost feels as if the mind and body want to develop in this way, which might explain why play feels so good and brings people such joy.

Play is as matter of performing work on the fundamental worldview at the base of your actions, shifting your perspective to find and develop areas where your perspective overlaps with others, and imagining the unknown into reality. As the interface for doing this, the human body is the ultimate alternative energy, and play is the catalyst that activates it. The question is when, where and how we can find and create structures that better enable the powerful transformations made possible by play.

Zack Wood has been researching festivals of games and play across Europe and America since 2014 and is the author of a chapter on these festivals in the recent book “Towards Broader Definitions of Video Games“. He is an artist and game designer from the US, currently based in Berlin. His work can be seen at wzackw.com.

Thank you Zack! I love this and will put it on the Share! List.

Thank you, Cynthia, I’m glad you enjoyed it. And I’m looking forward to doing some InterPlay at CounterPlay next month!