Wetiko:

Energy, Domination and

Human Societies

By Martin Kirk

May 9, 2016

We are transforming. Everything.

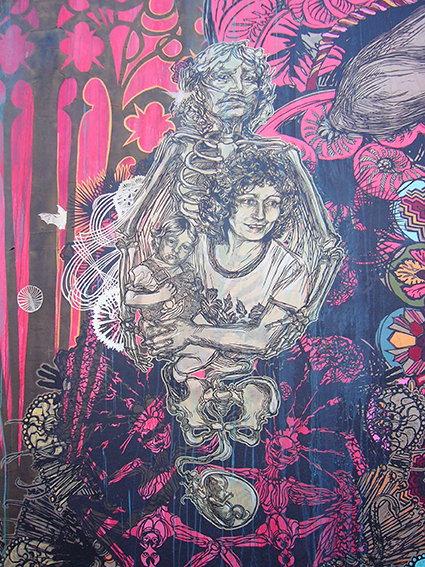

When a caterpillar becomes a chrysalis, its physical form dissolves into a sort of primordial goo and then re-forms as a butterfly. The entire life-system reboots its organising principles. It changes how it looks, the way it moves, how and what it feeds on; it is, to all intents and purposes, a wholly different thing. The butterfly is made from the same basic material as the caterpillar, but that material is organised so differently from what came before that it is unrecognisable in almost ever way.

There is a concept common to many North American Indigenous nations that provides a useful way of understanding the organising principles we are – hopefully – transcending. It is variously called wetiko, windingo, and wintiko, depending on the nation. It is a strange, often frightening thought-form. It is not bound by Western scientific frameworks, but rather has grown out of profoundly non-Western worldview. As such, it is particularly useful for Western, non-Indigenous audiences because it can, if approached with an open mind, free us from some of the assumptions that limit our thinking.

We cannot understand the myriad possibilities for what manner of butterflies we may become if we are tethered too tightly to our old caterpillar ways of thinking and being. Wetiko is a vehicle to help us understand where we have come from and why, and help us shape – such as we can – where we may be going.

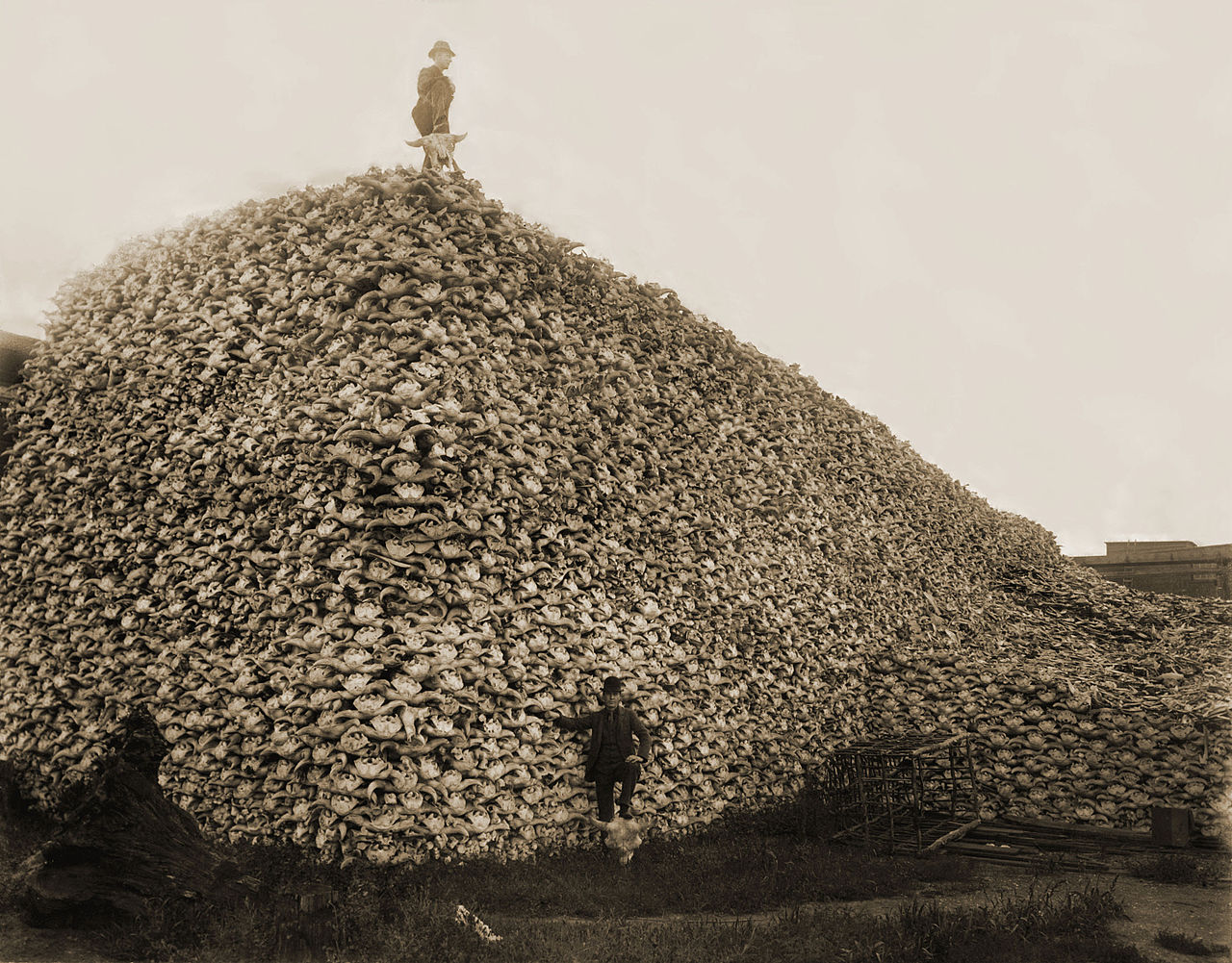

“We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and the winding streams with tangled growth as “wild.” Only to the White man was nature a “wilderness” and only to him was the land infested by “wild” animals and “savage” people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved was it “wild” for us.”

Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle, Bison Books (2006)

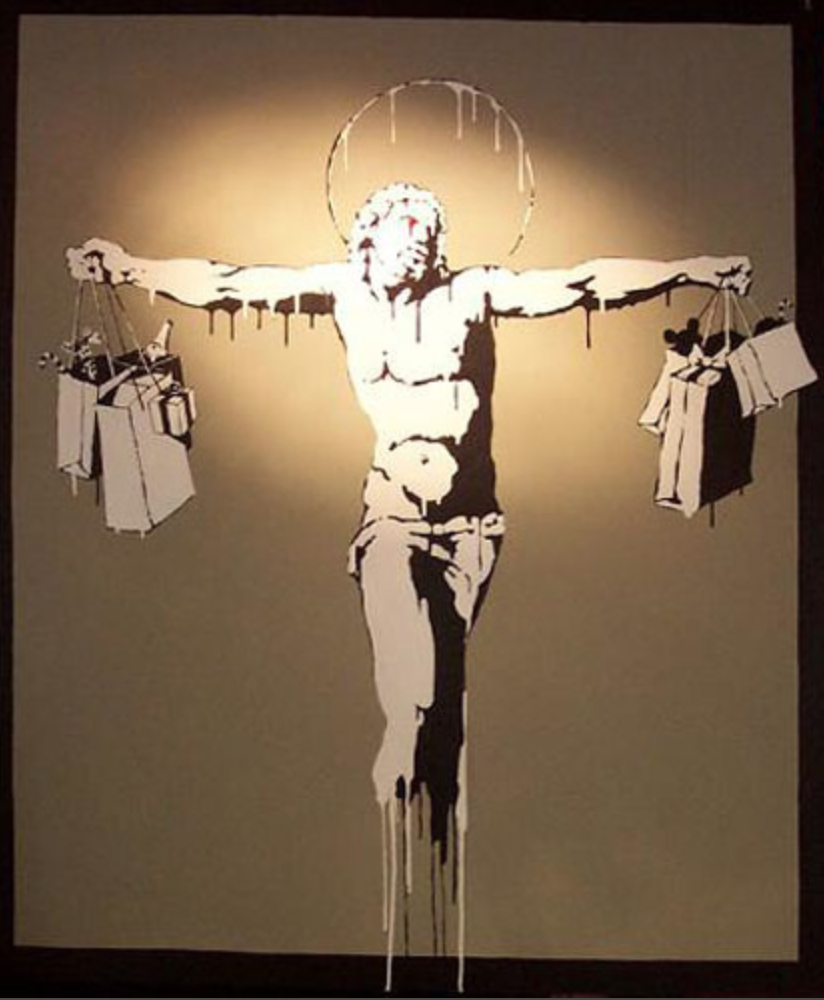

It doesn’t ultimately matter whether the sources of energy are renewable or finite. The point isn’t what type of energy is used, but rather the intentions driving that use. A wetiko-infected entity will feel it necessary and moral to consume at the fastest possible rate their technology allows and transform all efficiency gains into ever-more consumption. If the intention is unchained from any sense of limit, and driven by a desire for excess, selfish and self-aggrandizing consumption, we are dealing with wetiko.

The point is, the epidemiology of wetiko has left clear tracks. Although it cannot be pathologized along geographic or racial lines, the cultural strain we know today certainly has many of its deepest roots in Europe. It was, after all, European projects – from the Enlightenment to the Industrial Revolution, to colonialism, imperialism and slavery – that developed the technology that channelled the energy that facilitated the spread of wetiko culture all around the world. In this way, we are all heirs and inheritors of wetiko colonialism.

We are all host carriers of wetiko now.

So when people tell us that the growth is the answer, or market knows best, or technology will save us, or philanthrocapitalism will redistribute opportunities, we have to understand that all of these seemingly common sense truisms are embedded in the Wetikonomy. And the more these growth/market/technology/philanthropy based dreams of salvation are presented as ‘unchangeable’, the more often we’re told, ‘there is no alternative,’ the more we should question. There is actually a beautiful irony in the fact that when we know what we’re looking at, such statements are like signposts for where the greatest change is needed.

Instead of swallowing these ‘lose even if you win’ ideas, we can target the wetiko logic where it most powerfully lives, for example, in the idea of GDP as a measure of progress. Our politics start to become the politics of transformation when we set an intention to change the rules that give life to wetiko logic.

Martin Kirk is Head of Strategy for /The Rules, a global network of activists, organisers, designers, coders, researchers and writers dedicated to changing the rules that create inequality and poverty around the world.

Very Enlightening indeed. Thank you for Sharing your views. Would love to keep this in mind. Look forward to Reading more on this. Regards

Sekhar